Like many Houstonians tired of being indoors and pleasantly surprised by the cool weather last weekend, I took to our city’s increasingly well-developed hike and bike trails to seek fresh air and nature during these often too-isolating times.

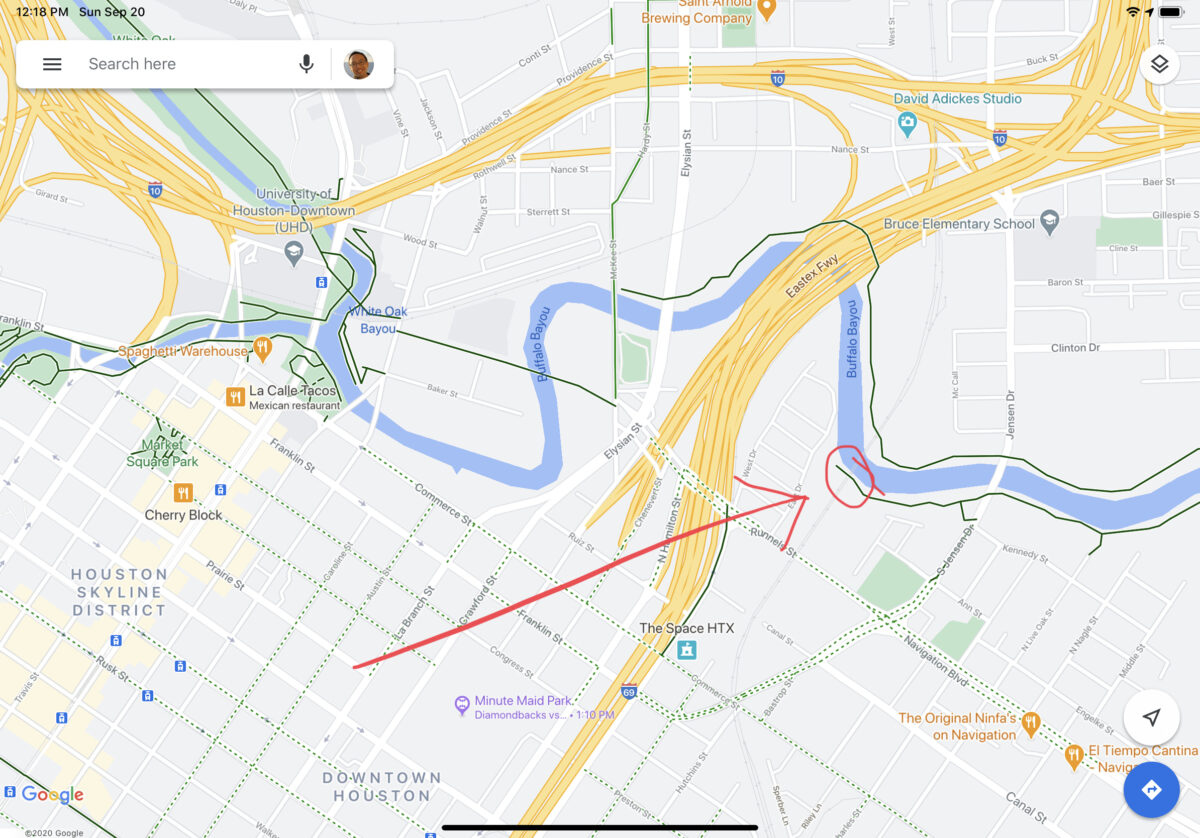

At approximately 10:30 in the morning on Sunday, September 20, 2020, I was ambushed, assaulted, and robbed on the Buffalo Bayou trail near Guadalupe Plaza east of downtown Houston near the intersection of Jensen Drive and Navigation Boulevard.

The assailants were three young males in their teens or early 20s. They were waiting under the Union Pacific railway bridge—a section of the trail with limited outward visibility and no easy detour.

The assailants were three young males in their teens or early 20s. They were waiting under the Union Pacific railway bridge—a section of the trail with limited outward visibility and no easy detour.

Moments before I passed him on my bicycle in the tunnel, the oldest assailant threw another bike in front of me, which caused my bike to flip and me to crash. My riding companion rode up to my defense and was immediately assaulted (punched) by the assailants.

In what seemed like less than a minute, the three thieves rode off with our bikes and personal possessions in the attached bike bag, which included a cell phone, sunglasses, locks, and of course our Covid face masks. I had originally planned to bring my dog with me on this ride in a trailer, but luckily did not.

The attack felt like a scene out of a war movie—a convoy is driving down a well-known route only to have their path suddenly obstructed so that they could be ambushed by concealed attackers.

But fortunately we weren’t killed, and this scene unfolded not on TV or in a literal war zone but in downtown Houston, on a well-signed bike trail—less than 1 mile from the headquarters of the Harris County Sheriff’s Department, less than 2 miles from the headquarters of the Houston Police Department (HPD), and in broad daylight.

While the attackers had my phone, they did not take my cellular-connected smart watch, which I I immediately used to call 911.

To my despair, the 911 operator said she could not access my GPS coordinates, was unfamiliar with Houston’s bike trails, and could not even look up a nearby METRO bus shelter number. She did not pin down my location until I ran to Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church and provided her the road intersection.

There just happened to be an HPD officer passing by the intersection who immediately provided assistance, and the Houston Fire Department (HFD) quickly arrived minutes later to assess our thankfully minor, physical injuries. Both the HPD and HFD first responders were first rate.

This was not a random crime of opportunity. These attackers knew what they were doing; they carefully selected the location, prepared their tools of attack, and were able to quickly get away.

I called the Houston Police Department Robbery Division on Tuesday morning, September 22, 2020. The officer who promptly answered informed me that the responding officers had investigated the crime scene and collected evidence but that no investigator had been assigned yet.

I called the Houston Police Department Robbery Division on Tuesday morning, September 22, 2020. The officer who promptly answered informed me that the responding officers had investigated the crime scene and collected evidence but that no investigator had been assigned yet.

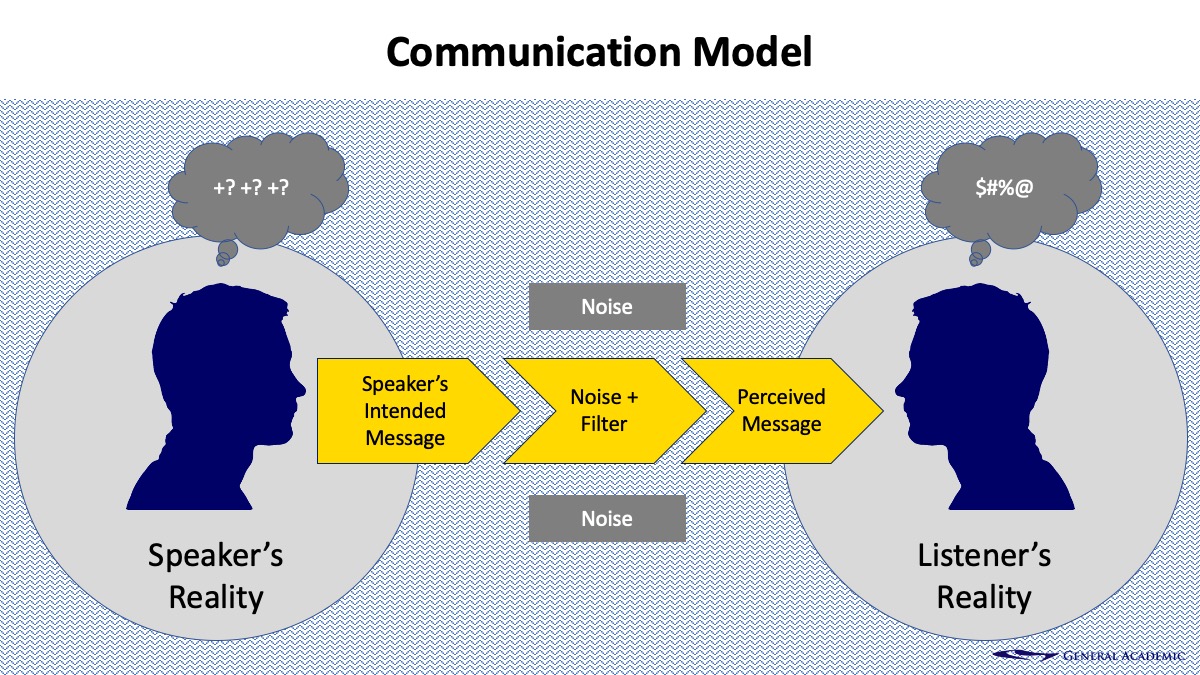

He also volunteered more safety tips than he was likely trained to share including his views on political correctness and how it can distort one’s sense of personal security.

I honestly don’t think he meant to come off how he did, but during those 12 minutes I felt like I was being berated for allowing myself to be victimized.

Update 9/25/20

After thousands of people read this article and KHOU aired a story, another victim reported to me that he and his friend were also attacked and robbed at the exact same location in a similar manner just days before we were. Stay safe Houston and avoid these sections of the trails.

Update 3/1/21

Another cyclist was attacked and robbed at the same place by suspects fitting the same description as my attackers.

We Are Victims

We’re fortunate in that the superficial nature of our bloody knees, cut hands, and black eyes allows us the luxury of being able to think about what we could have done differently and why it happened to us when it happened. No one likes being labeled a victim, but when it happens we have to learn to cope with it.

We’re fortunate in that the superficial nature of our bloody knees, cut hands, and black eyes allows us the luxury of being able to think about what we could have done differently and why it happened to us when it happened. No one likes being labeled a victim, but when it happens we have to learn to cope with it.

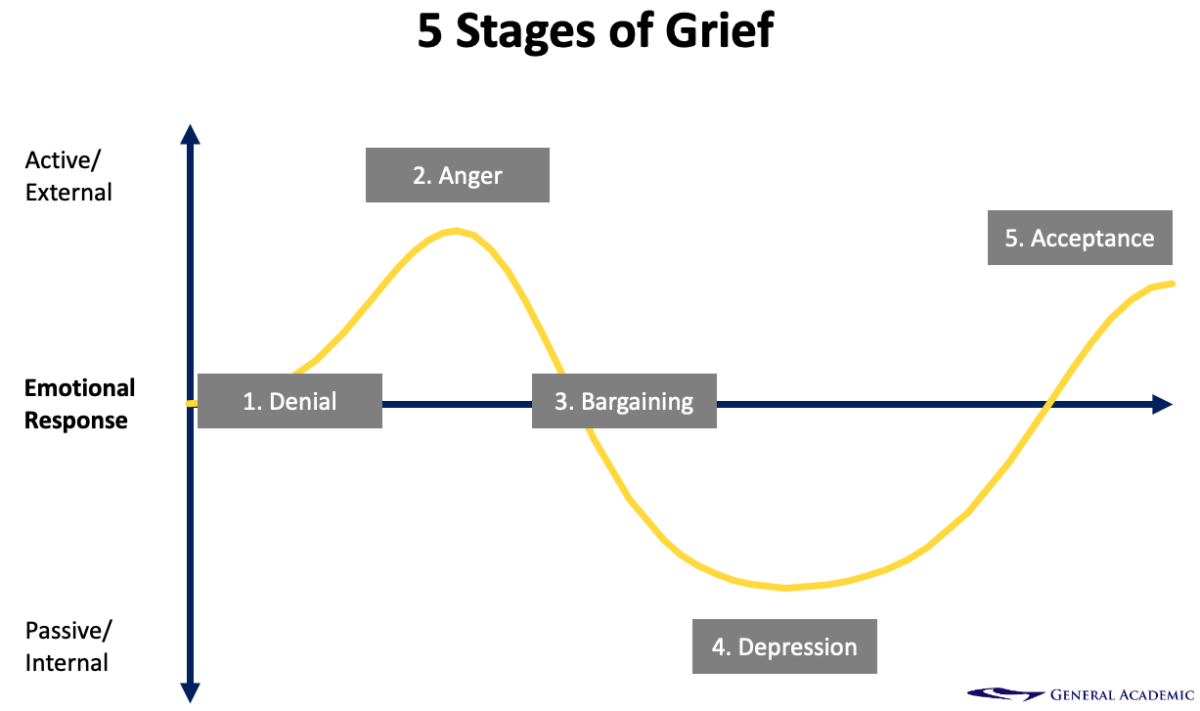

One of my favorite classes as an undergraduate at Rice University was PSYCH 231 – Industrial and Organizational Psychology. I liked it because I felt like it covered a lot of topics applicable to regular life like, “how to convince a team of your idea” or “why losing a job is so demoralizing,” and even Kübler-Ross’s “5 stages of grief” model. I knew that I would likely experience some form of these stages:

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

Denial came quickly for me. It started when the police were trying to write up their report on the street. I kept telling them to waste no time in tracing my phone and looking for our highly visible bikes; I thought that surely both actions would be both easy and fruitful. I was in denial that I had been so easily and successfully victimized.

Anger followed soon after when I got home and realized that my phone presented tracking data that was three days old and that by now my bike would be nearly impossible to hunt down in the fourth largest city in the nation—during a pandemic and in the depths of an economic recession.

I was angry that it happened to me at all when I like to think of myself as a careful and informed person, which of course leads to bargaining or rationalizing the emotions that I felt:

- Why did I take this trail in the first place? I’ve lived in Houston for 17 years; I know what some areas of town can be like.

- Why did I not turn around when I saw a group of young men loitering so close to the trail and eyeing me?

- Why was I unable to prevent from crashing and falling off my bike?

- Why did I not put up a better fight?

- How is our society so broken that these young criminals were “forced” to prey on unsuspecting passersby?

I’m hopeful that the depression phase won’t be so severe because a) I know to look out for it b) I’m writing this article and talking with friends and family to express my feelings and c) I don’t get depressed easily. But I have definitely felt flashes of depression already.

I think part of the process of navigating the depression phase is about understanding how isolating the experience can be. When you are at the receiving end of some terrible act, you feel personally attacked and violated. And it’s a huge deal to you; it maybe alters your entire outlook on life.

But to the outside world—in the US at least—the immediate assumption among others is often, “how did you not assume enough personal responsibility to allow that to happen to yourself?” And even if you didn’t do anything obviously wrong, how does your one grievance compare to everything that could go poorly and is going terribly for hundreds of millions of unfortunate people in the world?

But does this realization of the minor role you play in a world full of horrors minimize the feelings that you have?

Acceptance is the stage that perhaps is open up to more criticism and interpretation. Yes, I agree that it’s important to accept what has happened, but that doesn’t mean I have to accept that it’s okay or that these types of violent crimes should happen to people.

We Can Do Better

I am not content to say “woe is me” or nod when someone says, “it’s not the first time I’ve heard of this happening.”

I am not content to say “woe is me” or nod when someone says, “it’s not the first time I’ve heard of this happening.”

We can do better than that. We are the cyclists, the neighbors, and the inhabitants of the City of Houston, and we shouldn’t have to ride in fear of brazen, planned ambushes during broad daylight along well-known trails.

I hope that my experience will serve as a warning to other riders and as a call to action to city leaders:

- Bikers need better maps and safety information to make more informed route decisions.

- Criminals should not be so emboldened that they plan and carry out such audacious attacks.

- Emergency responders should be empowered to locate victims not on a road.

While I’m not so naive to think that anything will change quickly—particularly during these increasingly troubled times we live in—here are some “hindsight” tips to help prevent others from enduring my pain.

Be Vigilant and Prepared

- Be wary of people loitering within striking distance along a trail.

- Avoid areas with limited access and visibility like under bridges.

- Carry some form of personal protection like mace.

- Stick to well-trafficked areas in neighborhoods you know.

- Ride with many other people when possible.

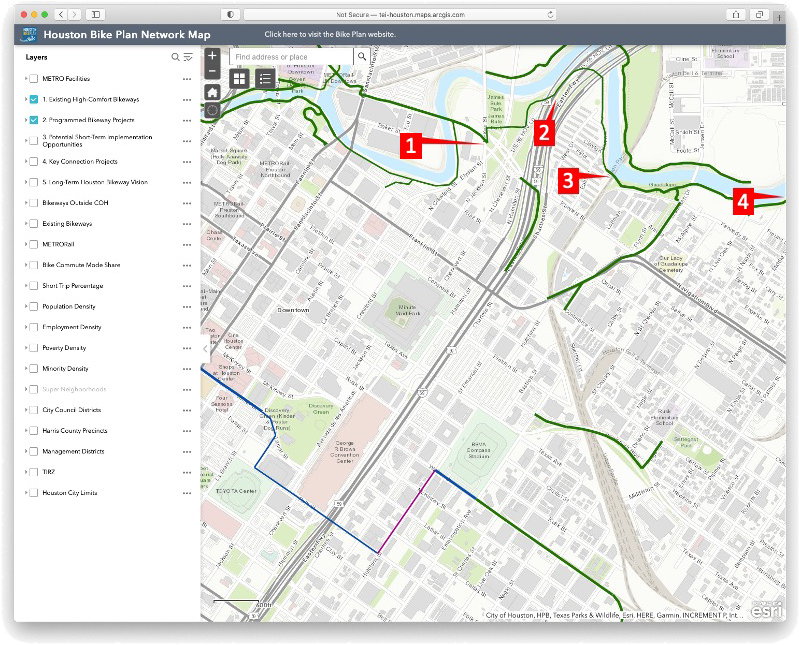

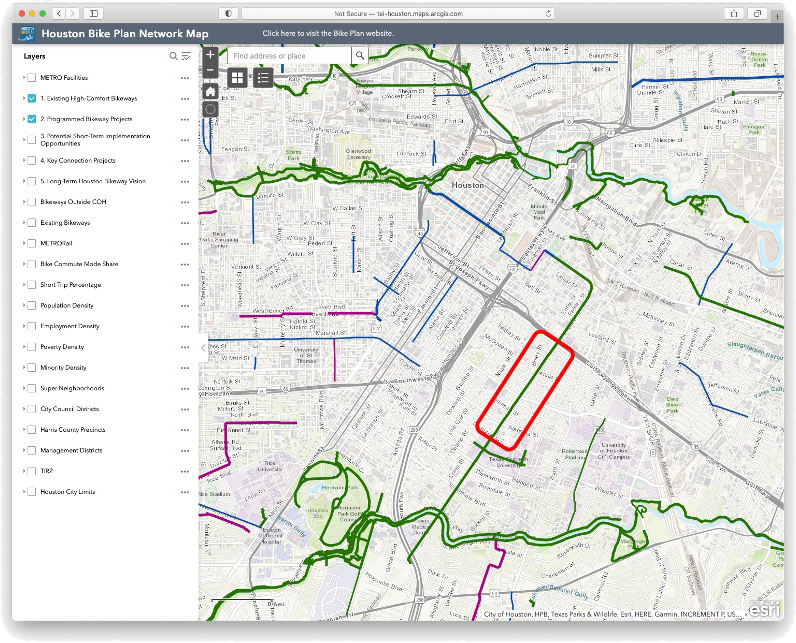

The Houston Bike Plan map is terrible. By default it shows 5 layers including “programmed bikeways, potential opportunities, and long term vision.” In short it shows a lot of routes that don’t exist. But in other cases it fails to show routes that are recently finished like the Gray Street dedicated right of way. It’s simply unreliable. Here are some tips from my observations:

Avoid the Buffalo Bayou Trail east of University of Houston Downtown

- The road intersection of Runnels and Elysian at James Bute Park is under construction and difficult to navigate.

- The trail that leads under the interstate interchange can harbor many unpredictable, psychologically-unstable, tented residents.

- The intersection of the trail and the Union Pacific Railroad bridge is where we got attacked. It is easily obstructed, has limited visibility, and not quickly accessible by a main road.

- The trail is not maintained north of Rainbow Ceramics close to the intersection of Navigation Boulevard and North York Street. The pavement turns into a an extremely narrow, overgrown dirt path marred by large rocks and roots.

I’m saddened to make this recommendation, as this trail actually leads to some very wooded areas (see featured image), which easily allow you to forget you’re in the 4th largest city in the United States, and I actually liked Marron Park at the end.

If you want to explore EADO, stick to the main roads like Navigation Boulevard, which doesn’t have an excess of automobiles and tends to be well trafficked by other bikers.

If you want to explore EADO, stick to the main roads like Navigation Boulevard, which doesn’t have an excess of automobiles and tends to be well trafficked by other bikers.

Avoid the Columbia Tap Trail South of 45 and north of TSU

The trail leaves the road and becomes a dedicated off-street “high comfort bikeway” south of Interstate 45; it was the site of similar types of robberies in 2013. The crime rate remains high in the area, and the path crosses many neighborhood streets with poor signage. However, the surroundings improve dramatically directly adjacent to Texas Southern University (TSU).

Advocate for Safer Trails

A social policy graduate student could spend 6 years writing a thesis trying to identify what led this group of young men to think it was a good idea to commit a brazen act of violent crime in broad daylight. And it would probably require another 60 years to make real headway on the root causes. However there are certainly some easy to implement, relatively low cost measures that could be taken in the interim:

- Improve the maps. The city’s Houston Bikeways map should be maintained to reflect reality and not require a degree in GIS to decode. Ideally it would overlay with crime data from the Houston Police Department so that residents can make more informed route decisions.

- Patrol the trails. The Houston police have officers on bikes, but in the 200 miles I rode in the 8 weeks between July 20 and September 20, I never saw a single police officer on a bike (I look forward to being enlightened about how I’m wrong here).

- Place location markers along the trail. For example, there could be a marker every 25 feet with a number by which 911 responders could locate a victim, “Hi, I’m at trail marker 125.” 911 responders would have to be trained on how to access and use the data.

- Place “blue light kiosks” along the trail. These kiosks with phones (and sometimes cameras) are a mainstay of college campuses. They serve as deterrents and provide a way for victims to both call for help and be easily located. However, implementing these kiosks would be expensive and technically challenging given the propensity for flooding along many of Houston’s trails.

Role of Big Tech

If Google and Apple want to monopolize maps and directions, then they should at least figure out a way to layer crime data with their maps and take it into account when recommending directions. Big Tech should not recommend routes that go through well-documented, high crime areas.

Coda

March 22, 2021—Six months have now passed since we were attacked on the Buffalo Bayou trail. I got considerably more depressed than I had anticipated in the original writeup above. In my initial effort to get answers and prevent future attacks, I learned three important things:

- The Houston police do make an effort to help.

- But no one coordinates the safety of Houston’s parks.

- And the justice system wasn’t going to provide me with any satisfaction.

Shortly after tens of thousands of people had shared my writeup on social media and KHOU aired a story, a captain from the Houston police reached out directly to me. She offered her sympathy and explained that her department does in fact patrol the parks and she herself rides the Buffalo Bayou trails. However, she lamented that there is only so much her squad can do. Furthermore, I was contacted by a Houston Police Department detective within a couple days of the incident, and he said that I had, “gotten someone’s attention.” Friends who live in EADO said that they suddenly started seeing police on bikes.

Last fall I talked with a senior representative of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership, the non-profit that manages Buffalo Bayou Park. Buffalo Bayou is a public-private partnership, meaning that the land isn’t actually owned or managed by the city of Houston. This representative told me that there’s virtually no coordination between her organization and the relevant public safety offices including the Harris County Sheriff’s Department or the Houston Police Department. In fact, she lamented how difficult it was for her to secure police to regularly patrol.

I actually got the name, address, and credit card information for someone almost certainly involved in the attacks. Yet, the police did not make much progress with that information, because they were unable to secure a search warrant.

We purchased our electric bikes from a small company based in Vancouver, Canada. It occurred to me that the thieves might contact the bike company to secure replacement charging equipment. My hunch was correct; according to the bike company, they had received an order within 4 days of our attack for bike charges from a Houston customer who had never ordered bikes from them.

The bike company relayed this information directly to the Houston police within two weeks of our attack. Some bureaucracy happened and by mid-October I was informed that the police were unable to secure a search warrant because the “information was stale.” And with that ruling from the Probable Cause Court judge, the case on our attack was closed. I attempted to contact the Harris County District Attorney, but I never got a response.

The friendly Canadians at the bike company never shared with me the exact address, but they did describe it on a map, and it aligned perfectly where a previous victim said his stolen phone pinged from before it was turned off. The officer investigating our case also never shared the address, but said the names provided were known criminals.

One last thing I learned—Amazon sells mace, in a variety of colorful cases, at very affordable prices, and with same day delivery.

—

*Victim’s Note – After several pointed critiques, I edited this article on September 23, 2020, to de-emphasize the HPD officer’s comments about what I should have done to prevent the attack. It’s certainly true that one officer does not represent the entire HPD or law enforcement community, and I do not think that the take-away from my story should be about polarizing political issues. I just want you and I to be able to walk and ride around our city’s parks in broad daylight without fear of ambush, which probably includes adding police/constable/safety officer bike patrols to trails.

- Also updated on September 24, 2020, to include new thoughts as I navigate the depression phase.

- And on September 25, 2020, with the information from another victim at the same location just days before.

- And on March 22, 2021, with information from yet another victim at the same location and with lessons learned.